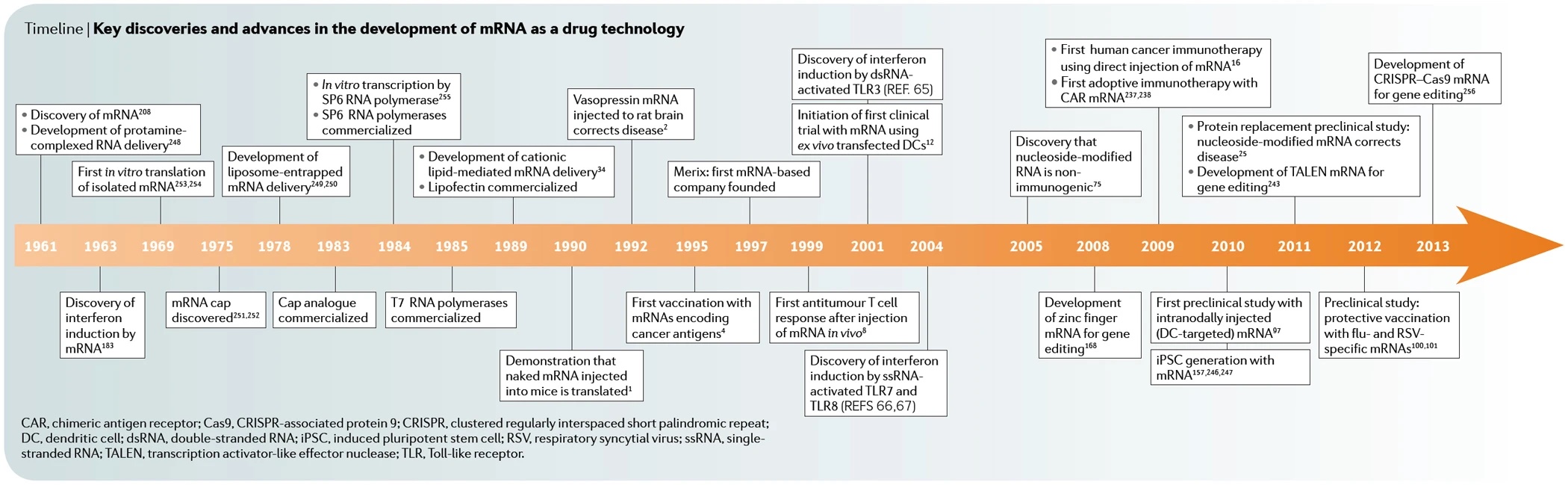

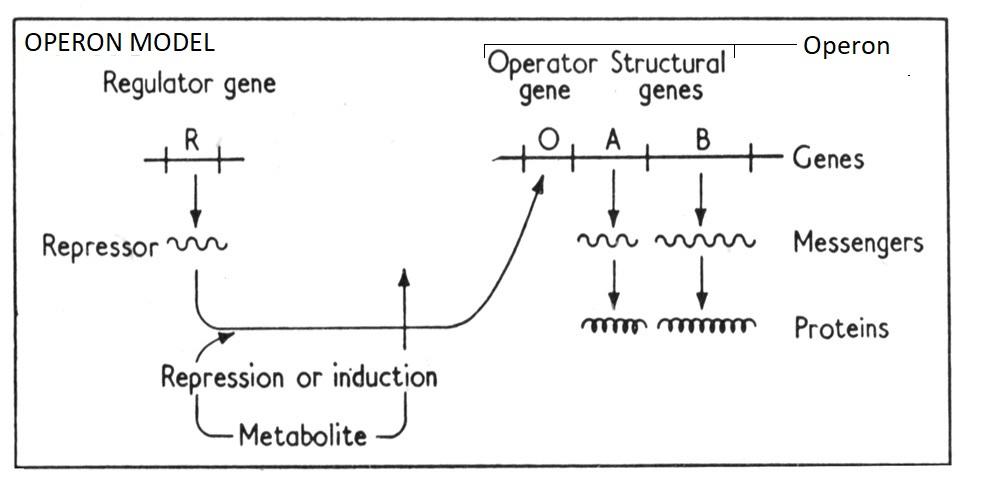

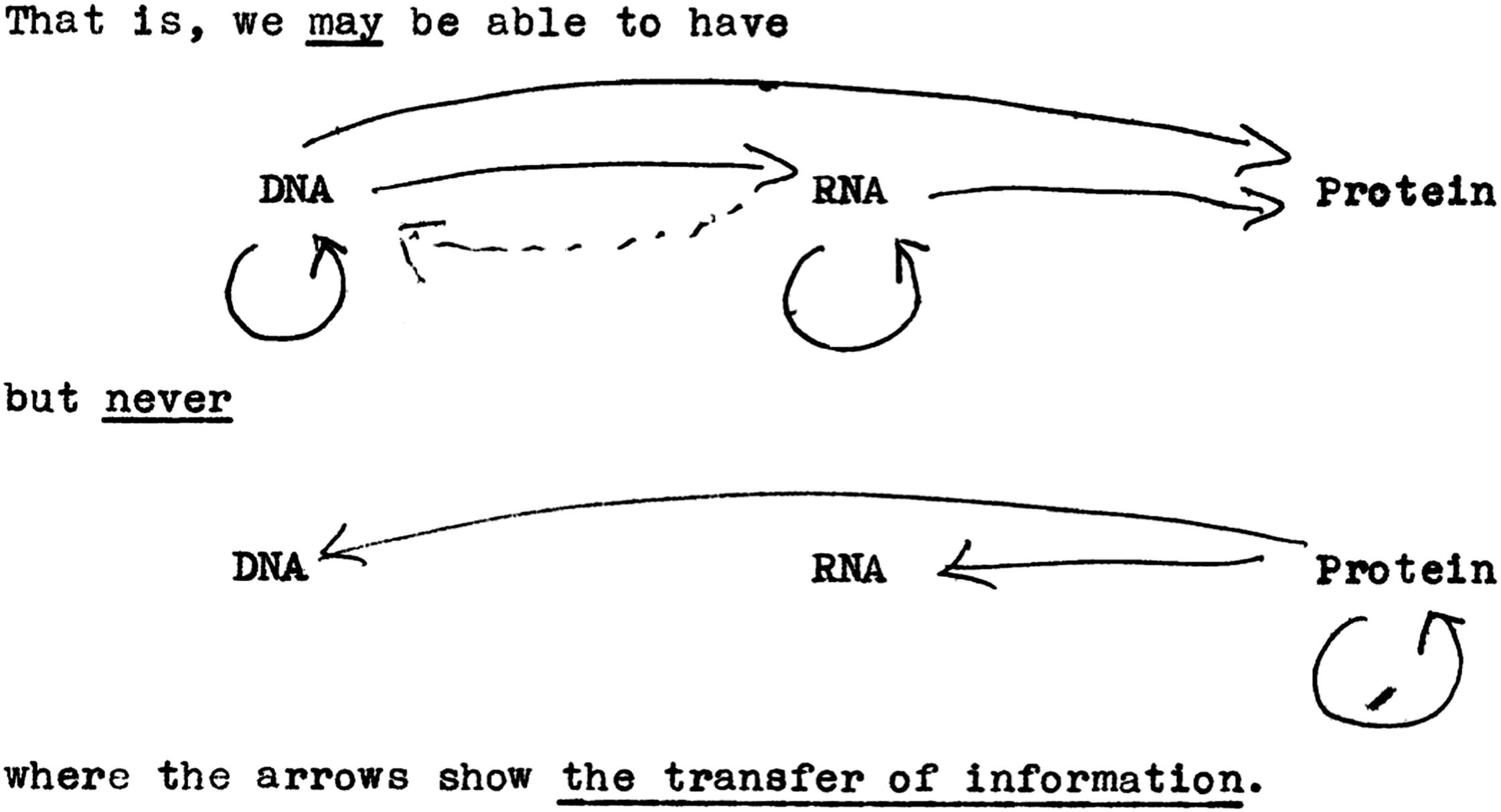

mRNA technologies that have led to today's Covid-19 vaccines have been researched and developed for about 30 years. More details on this and other RNA therapeutics in an upcoming blog post. In 1990, the first attempts were made to use synthetic mRNA so that an organism could make a protein programmed by it (see also Understanding Biotech). They took place successfully in mice, but undesirable side effects still occurred with inflammation. This was a completely natural reaction, since the immune system has been trimmed for billions of years to eliminate genetic material from viruses. It then took years of research to find out how cells or the immune system recognize foreign RNA in the first place.

Work on this was carried out by scientists in the U.S. at the University of Pennsylvania, among others: Drew Weissman and Katalin Karikó are often mentioned here, although they were not the only ones. By using chemically modified RNA building blocks, they succeeded in 2005 in suppressing the undesired strong immune reaction to the RNA itself (not to the protein programmed via it). Based on these findings, the U.S. biotech company ModeRNA was founded in 2010 with the goal of letting the body make its own protein drugs. "We were asking, could we turn a human into a bioreactor?" They struggled with how to get the RNA into the right cells as efficiently as possible but with few side effects. And they learned that mRNA had no lasting effect, for example, to replace a missing blood clotting factor.

The focus soon turned to vaccines that, after being administered once or twice, help the immune system to acquire a kind of memory that enables it to react again and again to an encountered and thus known antigen. Antigen stands for "antibody-generating". These are substances that stimulate the immune system to produce defense substances (antibodies). Antigens can be surface molecules of viruses or bacteria, but also flower pollen if an allergy is present.

The fight against other viral diseases with the help of mRNA technology is in the starting blocks: HIV, herpes, Zika and other viruses are to be targeted. Malaria is also a focus. In addition, an application against heart attacks or rare inherited diseases is conceivable, although there is no guarantee of success. Infections are a relatively "simple" indication, because the target (molecule) is quite well known. Especially with cancer this is not so easy.

Recently, a combination of mRNA with the gene scissors CRISPR has also been considered with the aim of carrying out gene therapies for the treatment of HIV and sickle cell diseases or other hereditary diseases. In addition to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.S. startup Intellia Therapeutics is looking into this. And the Weissman professor at UPenn. A tool based on mRNAs in lipid particles that can fix malfunctions in the human blood system could be as lucrative as pandemic vaccines.

The original article written in English by Antonio Regalado, on which this blog post is based, can be found here. However, he hardly addresses the achievements in Germany: BioNTech is only mentioned briefly and CureVac's significant role is omitted completely. This is unfortunately also the case in some other Anglo-American articles. Finally, misrepresentations in the U.S. that the vaccine was developed exclusively by Pfizer (without mentioning BioNTech) could be seen critically.

Also in Germany researchers devoted themselves to mRNA relatively early on. In the summer of 1996, the Tübingen biologist Ingmar Hoerr decided to dedicate his doctoral thesis to the topic of RNA as a possible vaccine (see the extremely exciting biography of Ingmar Hoerr, written by the science journalist Sascha Karberg). In 1999, the first successes were achieved in the experiments and in 2000 he founded the company CureVac with the aim of developing mRNA vaccines, i.e. 10 years before the U.S. competitor ModeRNA. In a patent filed in 1999 and granted in 2005 on the transfer of mRNA using polycationic substances, Hoerr already described potential applications such as: Treatment of muscular dystrophies, insulin deficiencies, phenylketonuria, hypercholesterolemia and cystic fibrosis. He also mentioned its use in fighting cancer. In August 2000, the European Journal of Immunology published an article by Hoerr et al. in which the researchers raised the possibility of cancer vaccine development. By the end of 2019, CureVac is in the process of developing diverse vaccine candidates against rabies, avian flu, cytomegalo, chikungunya and Zika viruses.

The treatment of cancer was also the primary goal of BioNTech, founded in Mainz in 2008 by Özlem Türeci and Ugur Sahin. The researcher couple, working simultaneously at the University of Mainz, also focused on mRNA as one of several technology alternatives in oncology. They first published results on their mRNA experiments in 2006, and since 2013, the aforementioned Karikó has contributed her mRNA expertise to the Mainz team, while remaining loyal to the University of Pennsylvania as an adjunct professor. In addition to mRNA technology, BioNTech is pursuing other approaches to individualized cancer therapy such as programmable cell therapies, antibodies, and small-molecule immunomodulators.

Vaccines against infectious diseases were not so much in the foreground at the beginning, but were always part of the company's strategy. The rest is well known: in January 2020, the company began to focus on a Covid-19 vaccine and, together with its partner Pfizer, which was mainly responsible for the clinical trials, developed the vaccine COMIRNATY in record time, which received emergency approval in the U.S. and Europe in December 2020. ModeRNA also followed suit fairly soon, and so it is these two companies that currently dominate the mRNA vaccine market. CureVac is on the home stretch, with a regular approval of their mRNA vaccine in Europe imminent.

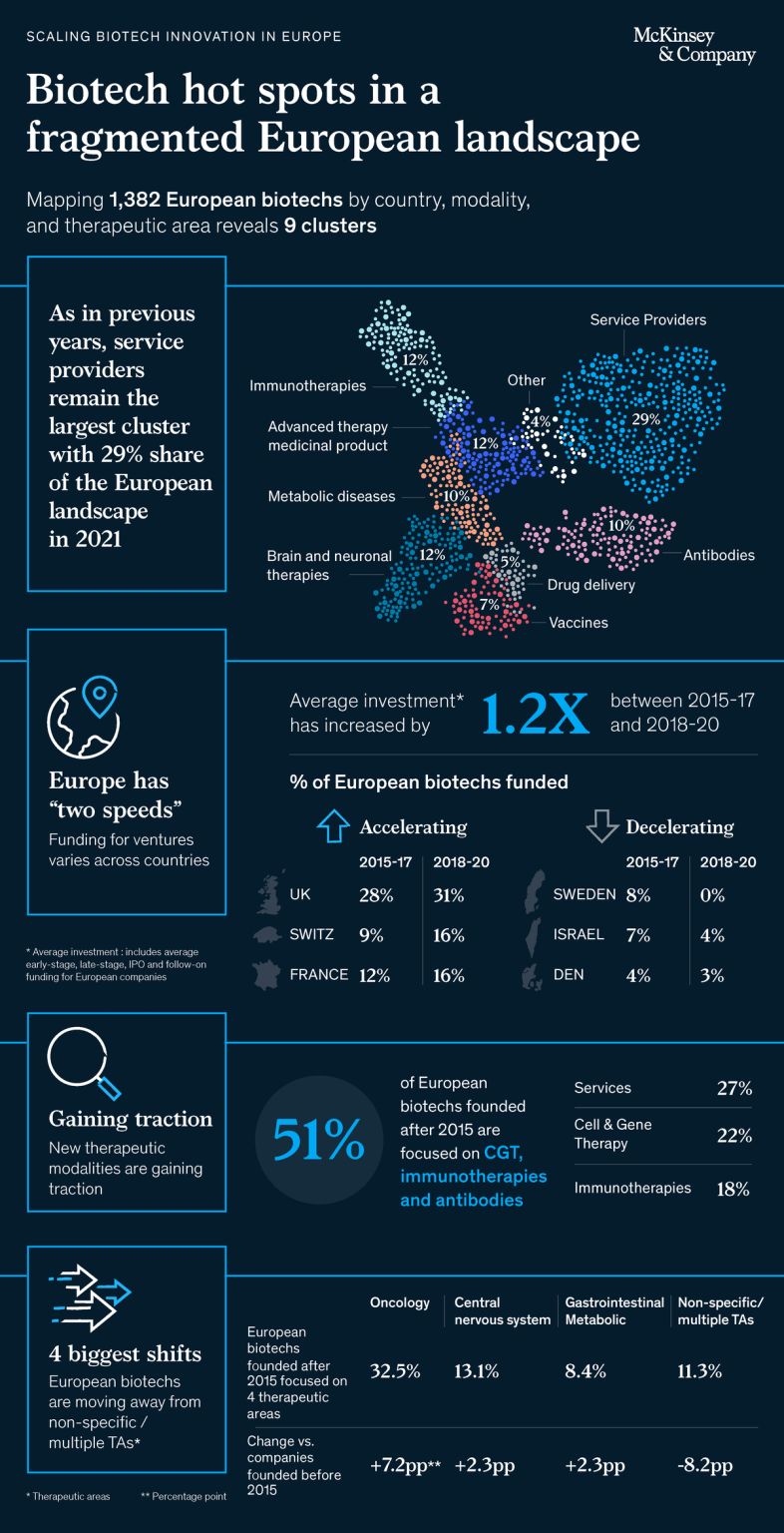

The German biotech industry can now be really proud; there is sufficient scientific potential. It can be done, but only with sufficient funding!

For example, according to BioCentury, CureVac and BioNTech have raised $1.7 and $1.4 billion in external funding to date. The largest amounts ever for German biotechs. Note, however, that ModeRNA is currently funded with a total of US$4 billion to date, including most recently a financial injection in May 2020 of more than US$1 billion from Morgan Stanley. In addition, there was nearly US$1 billion in grants from the U.S. government for the development of the Covid-19 vaccine.